The origin of the myth of Atlantis (draft)

The myth of Atlantis stems from two late Dialogues of Plato (Timaeus and Critias) [1], in which the philosopher wrote of a powerful Mediterranean empire that had conquered Egypt about nine thousand years earlier, before being defeated by the primordial Athenians and then destroyed by a cataclysm. The two dialogues praise the perfect social structure of the original Athenian polis (mirroring the one described in Plato’s masterwork, The Republic) and the heroism of the founding fathers of Athens (from whom the aristocrat Plato descended), giving the immediate feeling that the philosopher forged the legend of Atlantis to support his political ideal and celebrate his ancestors. [2]

Inventing stories to sustain a thesis was (and is) a common practice among writers of all times. And since the more the legends are believed, the more they support the author’s assumptions, various techniques have been developed to substantiate the forgery. The trick of modifying real stories (or believed so), by inserting own inventions in them is widespread and boasts illustrious examples. The Aeneid and the Orlando Furioso, to name just two classical cases, modified popular legends to glorify the ancestry of the commissioners. [3]

The scepticism of historians about the real existence of Atlantis is therefore well justified. The present article takes for granted the ‘invention’ of the legend, but tries to analyze whether it might contain references to actual events, even though artfully retouched. The working hypothesis is that Plato inserted the propaganda elements (the social structure of the ideal polis and his ancestors’ heroism) in a narrative of episodes believed real by his countrymen (the recipients of his message).

The whole story would therefore result in a syncretism blending mythological legends and impressive episodes, to be placed in a period compatible with the beliefs of the time. The myth of a flood hitting a primordial society grown too much in power and wickedness to deserve divine punishment was common among ancient cultures, including the Greek one.

Note also that the fellow citizens of Plato had a feeling of their grand past, witnessed by the mysterious cyclopean walls still visible on the acropolis, and had been shocked by the earthquake cum tsunami that erased the city of Helike in the Gulf of Corinth in 373 BC. (Paus. 7.24.12) (Pausanias 1918).

The Egyptians, at the time considered the oldest people in the world, provided themselves a valuable support to the myth of a vanished ancient civilization: their chronologies reported that their first pharaohs had been Gods (Van De Meroop 2011, p.18) coming from the West, a polite way of saying that their kingdom began when foreign conquerors with magical powers (i.e. unseen technologies) arrived in the area, bringing agriculture and new knowledge. For Plato’s fellow countrymen the birth of Egypt had a precise date: according to Herodotus, the human kingdom of Egypt (that followed the divine one) started 341 generations before his visit to Thebes (Book II, 142-144) (Herodotus 1890). Taking a generation gap of 25 years this meant about 8500 years before Herodotus, to be added to the divine realm duration. In calendar years, this would correspond roughly to 11,500 years ago (9500 BC), a period of substantial climatic upheaval.

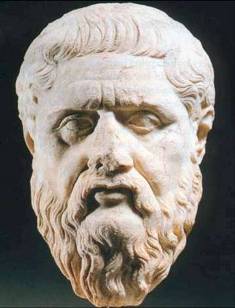

Aristocles, better known as Plato.

The gist of the story

In other words, in Plato’s times, the core of both the legend and the timing of Atlantis were somehow widespread among the literate Athenians, constituting a good base for building a fictional story [4].

Taking Plato’s geographical description at face value, nine thousand years before the visit of Solon at Sais (Tim. III 23.e; Crit. III 108.e) the Atlantic Sea was navigable (Crit. III 109.a) and, in front of the Pillars of Hercules (Tim. III 24.e) there was an island larger than Libya and Asia combined. This island was close to other islands and, ‘hopping’ through these, one could reach the continent that enclosed the vast ocean. The ‘capital’ of this empire was a small island, which ruled over the entire archipelago. On the continent, Atlantis ruled in Europe up to Thyrrenia and in Libya (Africa) from the Pillars to the border of Egypt (Tim. III 25.b). The main island of the archipelago had a large plain, three thousand stadia (approximately, 550 km) long and two thousand stadia (350 km) wide, surrounded by northern mountains and by a southern channel that ended in the open sea (Crit. X 118.b), with rivers, lakes, mountains and marshes, two harvests per year (Crit. X 118.e), elephants (Crit. VI 114.e) and exotic fruits (Crit. VI 115.b). Its first king had been Atlas (Crit. VI 114.b), who had perfectly organized the country, following commendable political principles, second only to those of Athens.

But when Atlantis wanted to conquer Egypt and Athens, the heroic Athenians resisted and defeated it, freeing Egypt too, that in the meantime had been subjugated. A little later, a violent earthquake and a flood destroyed Atlantis in a day and a night, leaving an impenetrable swamp in place of the island (Tim. III 26.d); Athens perished in the cataclysm too.

The key problem with the story is that the dating of the purported flourishing of Atlantis coincides with what we know to be the end of the Ice Age, a time before agriculture, when humans were still engaged in hunting and gathering, and therefore an unlikely time for an 'advanced' human society as the one described by Plato. What do we know about this crucial period, the end of the Ice Age? Are there any environmental factors which can help us explain elements of the myth of Atlantis, in particular its destruction by flooding and earthquake/volcanic eruption?

[1] The Platonic text analysed in this article is the translation by W. R. M. Lamb (Plato in Twelve Volumes 1925).

[2] Plato was the son of Ariston (whose pedigree went back to the first kings of Athens and, through them to the God Poseidon) and Perictione (belonging to another prominent family, related through Critias, to Solon, the legislator) (Taylor 1926).

[3] Virgil’s Aeneid attributes the origin of the gens Julia (the family of Caesar and Augustus) to Aeneas of Troy. In Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, a poem dealing with the Carolingian cycle, Bradamante and Ruggero are supposed to be the founders of the Este family.

[4] For a brief summary of Atlantis quotations by Herodotus, Plato and Diodorus, see Rapisarda (2015).