Although the Natufians or an unknown people living in the Nile delta are the most verisimilar candidates to impersonate the gods who brought civilization to Egypt, the climatic changes that occurred between fifteen and eleven thousand years ago regarded the entire northern hemisphere. More than ten thousand years ago, along three of the largest Asian rivers (the Yangtze, Indus and Tigris-Euphrates), agriculture emerged independently (Zhao 1998) (Gupta 2004) (Purugganan and Fuller 2009). Some time later, the same floodplains hosted the oldest human civilizations. It is enticing to imagine that along the corresponding coastlines (today submerged) a precursor phase could have taken place during the deglaciation process.

In other words, eleven thousand five hundred years ago, there might have been several “Atlantises” (some modern authors proposing them in diverse distant locations may actually be right), although none of them could have actually been related to Egypt, a possibility that instead was within reach for peoples living closer.

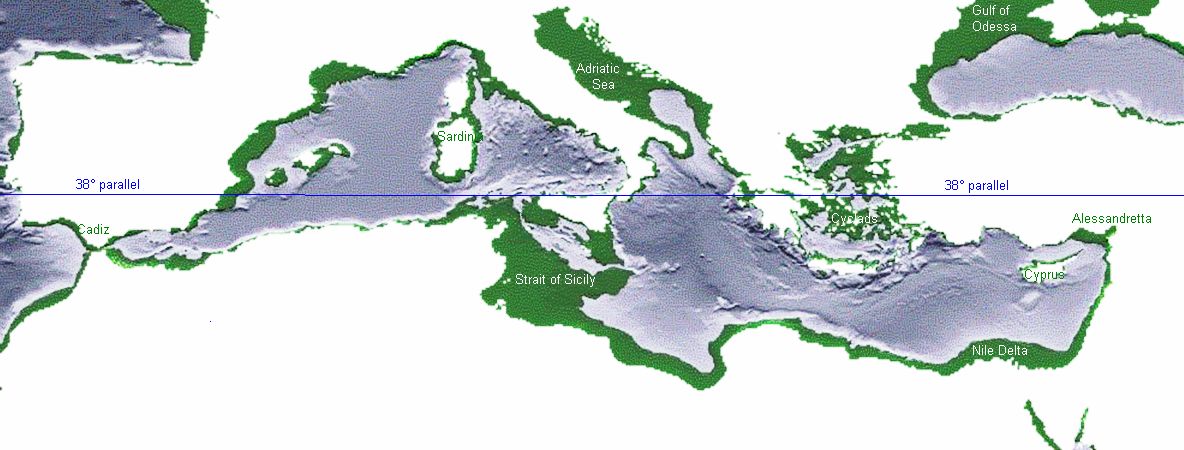

Indeed, although less likely, it cannot be ruled out that some of the innovative practices recorded in the Middle East twelve thousand years ago were replicated somewhere else along the Mediterranean coast, driven by similar geographic and climatic conditions. To this extent, the seabed lying south of the 38th parallel (see fig. 7) are the most indicated.

Many authors have already pointed to some of these regions as possible sites for Atlantis, supporting their choices with ingenuous arguments. It is likely that future underwater archaeological discoveries on the Mediterranean seabed will reinforce some of these hypotheses, re-engaging interest in the Platonic myth. To enumerate the suggested locations is beyond the scope of this article, but the interested reader may find most of them in the Proceedings of two dedicated Conferences (http://atlantis2008.conferences.gr/) in which they are unfolded quite exhaustively.

Nevertheless, among the possible candidates is a region where the hypothesis can be tested in a rather straightforward way, thanks to the presence of an obsidian source: the seabed of the Strait of Sicily. To this extent, two lucky accidents seem promising for the investigation:

a) The seabed of the Strait of Sicily is geologically rather quiet: it is almost possible to reconstruct the past shape of most of its coastline, taking into account only the eustatic factor (meaning that the isobath surfacing at a given sea level drop corresponds to the shoreline of the matching time) (Rapisarda 2015).

b) The island of Pantelleria, one of the four obsidian sources in the central-western Mediterranean, is one of the islets that dot the region.

Which isobath (or sea level) should indicate the shores of twelve thousand years ago? E. Bard, Hamelin, and Fairbanks (1990) estimated that before MWP 1b the oceans’ level was about sixty metres below today’s. Lambeck et al. (2004), through a geological model developed for Italy, later concluded that the same level was also valid for the Mediterranean Sea.[11] Still, Lambeck, like Ferranti et al. (2006), considered likely a marked subsidence of the southern border of Sicily, a factor that would add about a dozen metres to the eustatic value of the seabed near the southern coast of Sicily (leading the value of the isobath to choose there to around -70 metres).

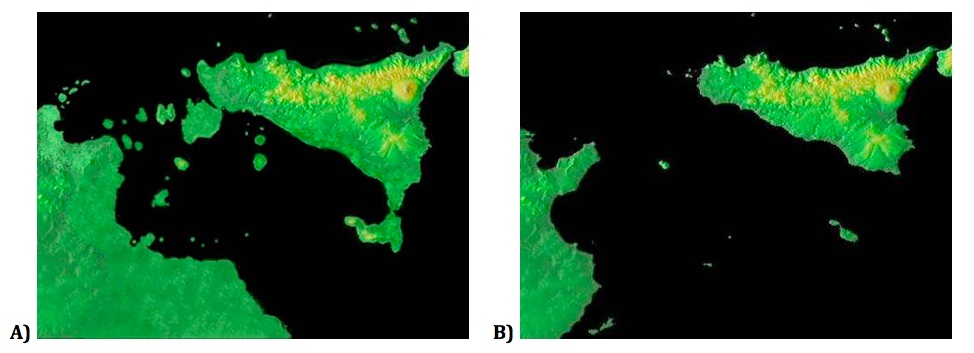

Taken with a grain of salt, Fig. 8 A) depicts a profile not very different from what might have been the Strait of Sicily during the Younger Dryas, showing an intriguing feature which would remain even if slightly different sea levels were selected. This feature is the presence of an archipelago, which would have permitted navigation between Tunisia and Sicily with land always in sight. An archipelago that a ten or twenty-metre rise in sea level would have modified, but not entirely submerged.

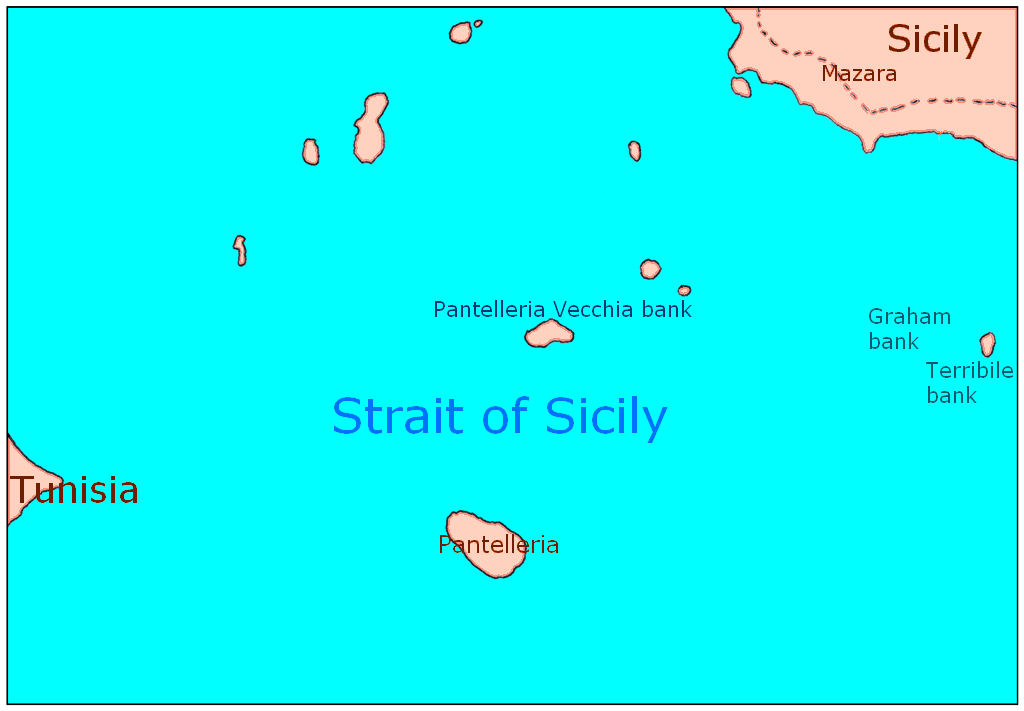

Occupying the maritime link between two continents would have been an advantage in a period that saw navigation progress rapidly. As we saw, in the Aegean Sea regular routes were being established to supply Melos obsidian to the mainland and, in the middle of the Strait of Sicily, there was an obsidian source in Pantelleria. It is unlikely that those living in the proximity would not have noticed it.

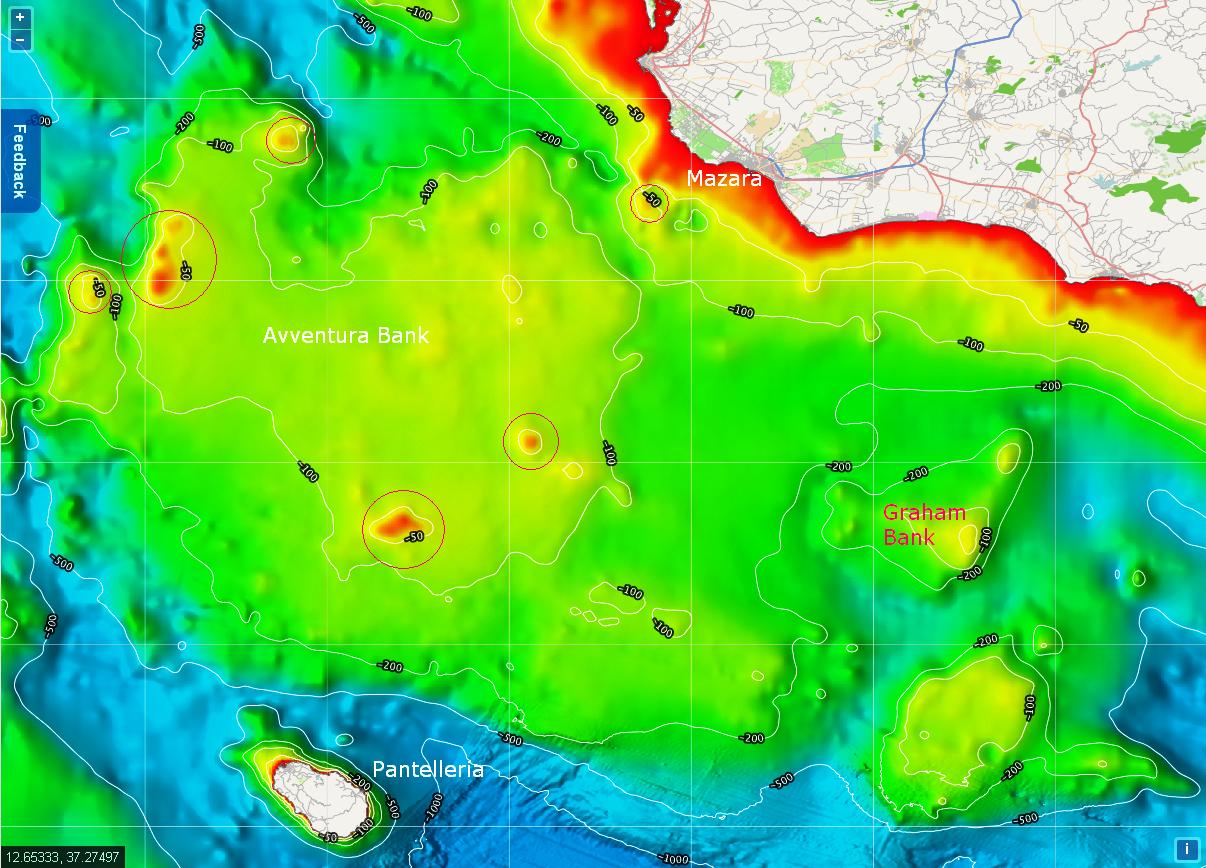

Between fourteen and eleven thousand years ago the region underwent significant changes. In the south western corner of Sicily, the large shallow seabed named Avventura bank (Fig. 9) was a peninsula (Fig. 8 A) before MWP 1a and later a group of islands. In front of it, Tunisia stretched into the sea with a large floodplain that included the island of Lampedusa. Portions of these plains survived the sea level rise of MWP 1a and experienced the warming of the Bølling-Allerød period.

A few millennia later, at the end of the Younger Dryas the geographical situation had changed considerably. With a sea level about fifty metres lower than today, most of the Avventura bank had been submerged, but an archipelago was still there to ensure the maritime connection between the two continents and an easy route to Pantelleria’s obsidian (Fig. 10). Its strategic importance is hard to deny and if the region was inhabited it is unthinkable that its most convenient spots were not, like the island closing a small southbound gulf near Mazara, or some of the islets on the route to Pantelleria.

The Avventura bank is partly surrounded by volcanoes, whose coastline history is too complex to reconstruct, since they have been subject to their own geological movements. It is interesting to note one of them: Graham bank, a submarine volcano located about thirty miles south of Sciacca. Most of the time it was entirely submerged, but during its occasional eruptions it may have managed to emerge (to become Graham Island or Isola Ferdinandea as happened in 1831).

Graham bank (Fig. 9) is one of the summit cones of a much larger submarine volcanic building, named Empedocles, located at 37° 10’ N, 12° 43’ E (of which the Terribile bank is another cone, for the moment quiet, see Fig. 10). In fact, the Strait of Sicily is dotted with volcanoes, submarine and otherwise (Pantelleria and Linosa are the two emerged examples). Needless to say, an explosive eruption from any of them, possibly accompanied by an earthquake and a tsunami, would have been a dramatic way to end human occupation in the region.

Since 2018 this site has been accessed times;

Atlantis has been visited times.